A LITTLE BIT OF VOODOO

In one of the biggest diet studies ever conducted, Schmitt and his team have collected the contents of over 16,000 blue cat stomachs. Schmitt, along with a few assistants each trip, electrofished the James, Pamunkey, Mattaponi, and Rappahannock Rivers.

“The process of electrofishing is voodoo,” jokes Schmitt. A submerged anode draws the fish close enough to boat for the assistant to net them, with the boat acting as the cathode. Little is known about why the signal actually stuns blue catfish, or why it only works at certain temperatures and salinities, but the surface, for about two minutes, is suddenly speckled with catfish after the shock.

Metal chains jangling against the railing, and the loud roar of the generator powering the electrode drowns out most of the conversation, but above the noise, Kim can be heard yelling out directions toward the emerging blues.

As Joe guides the boat towards the still-flailing fish, Kim uses a net to scoop the catfish into the boat. It’s a mad dash to capture as many as possible before they disappear beneath the surface again. Within minutes, the live-well, a metal box filled with river water on-deck, is filled with slimy, splashing catfish. From there, Schmitt and company shoot a stream of water into their stomachs to collect the contents, the “gagging.” They measure the specimen, and then “bag” the regurgitated lunch for later analysis.

The rancid smell of half-digested food is less than pleasant. "We have the reputation of having the stinkiest lab on campus,” says Schmitt. What they found in their bags turned out to be surprising at times, and concerning at others.

Free Invasive Species Removal Team

What about the humongous monsters gobbling up all of the blue crab and endangered fish?

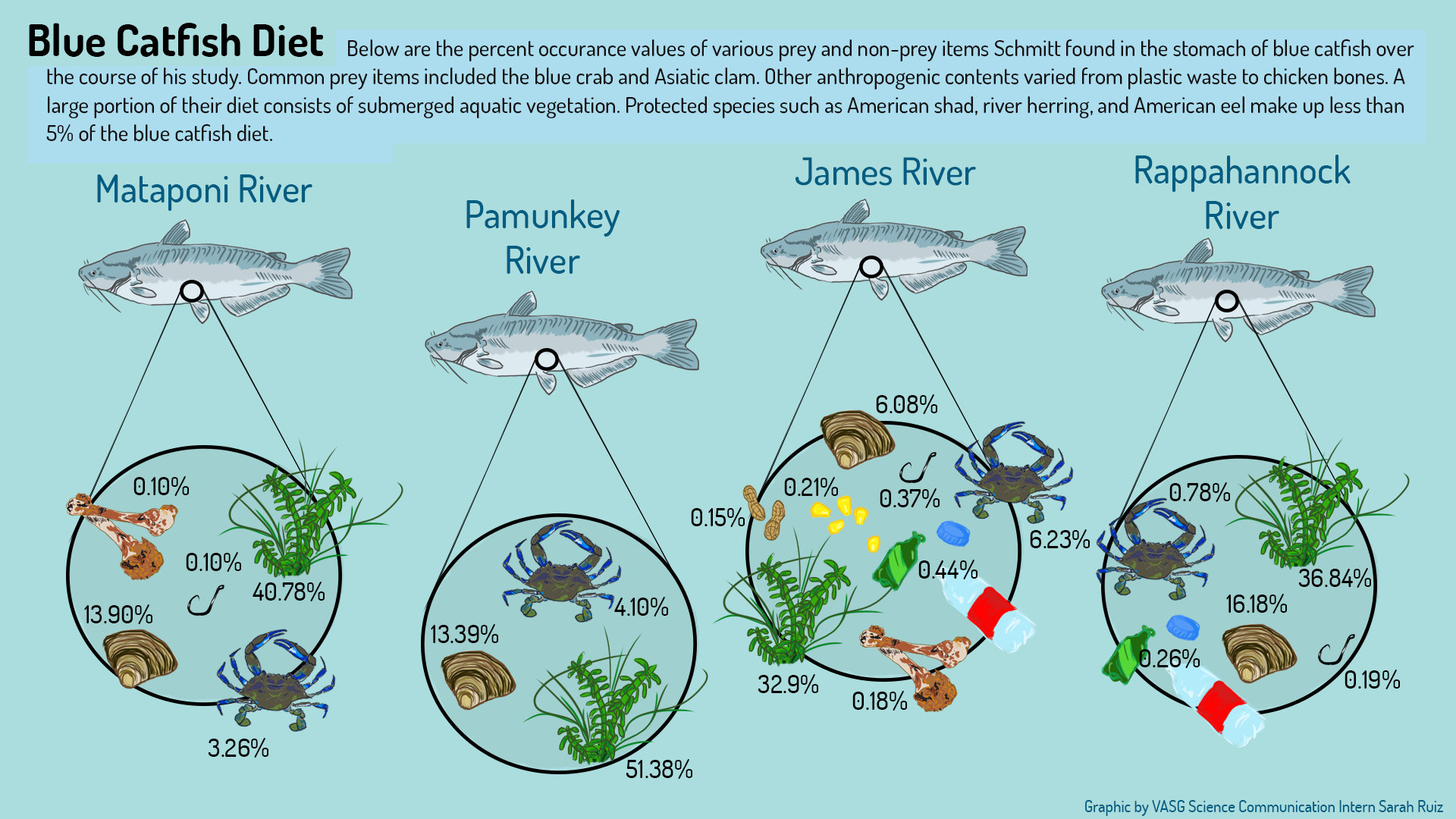

“The majority of the population in all rivers are omnivorous and they're not eating native fish species," Schmitt concludes, based on his findings. While the blue cats will sometimes grow large and become piscivorous—fish eating, in these rivers they are more likely to be small and omnivorous, according to Schmitt’s study.

The James River has proved to be problematic, however. "It stands out. We see more predation of native fish there. There are more piscivorous individuals, we have more big fish here than the other rivers. The James should be a river of high priority," notes Schmitt.

But the actual percentages aren’t as high as the “sensationalized” media coverage on blue catfish is claiming.

According to his study, Schmitt saw that 22 percent of the fish in the James had other fish in their stomachs, but in the York and Rappahannock Rivers, only two percent and five percent of the fish respectively had other fish in their bellies.

As for blue crab predation, “the probability of finding blue crab in blue catfish stomachs was as high as 30 percent in some conditions,” says Schmitt, but these numbers usually appear in the fall and winter when the vegetation is low, and only in certain locations, like around Hog Island. Overall, blue crabs were found in less than five percent of blue catfish stomachs, a stark contrast to the current narrative surrounding these whiskered fish.

In one of his 2017 publications, Schmitt noted that the “abundance of mature female blue crabs in the Chesapeake Bay continues to improve since the population declines registered in the late 1990s, even with increasing blue catfish abundance.” While blue crab is one of the largest economically important resources in the Bay, it appears as if there are only certain locations along the river where the blue catfish are seriously impacting their populations. But with the blue’s ability to survive in saltier waters, their impact on blue crab may increase with expanding territory—a theory yet to be explored.

Schmitt found that the most frequently consumed diet items were actually other invasive species, like Asiatic clams, hydrilla, and Brazilian waterweed. These species were found in 60 percent of stomachs. The blues may be acting as a free invasive species removal team, but their reputation in the media remains the same.

Schmitt is frustrated by the way the media has portrayed blue catfish. "The narrative was progressing faster than the science, so was the hype, the sensationalism, and fear. I'm not saying blue catfish are not problematic, it's just not as things were presented," he notes.